By Kevin Deutsch

[email protected]

New York State is on the verge of approving investigative DNA testing by a private company that can identity up to nine degrees of relatives based on a genetic sample—and which uses commercial databases containing the DNA of thousands of Americans—to assist law enforcement, Bronx Justice News has learned.

The Department of Health expects to approve licenses for Parabon NanoLabs—a Virginia-based company that markets forensic genealogical testing and consultant work to law enforcement—as well as a separate lab that handles most of Parabon’s DNA samples, once all required documentation is reviewed, Dr. Anne Walsh, Associate Director for Medical Affairs at the state Department of Health and head of DOH’s forensic identity section, said at a state forensic science commission meeting last month.

Parabon is the first private company to seek licensing for investigative genetic genealogy testing in New York, state officials said. If approved, it would face significantly less government scrutiny than public DNA crime labs like those run by medical examiner’s offices and law enforcement agencies, the officials said.

New York has a rigorous oversight regime for genealogical DNA testing—a process its forensic science commission and DNA subcommittee spent more than a year designing and refining. But those oversight standards would not apply to private DNA testing companies and labs, which have much greater leeway under existing state law.

New York’s Division of Criminal Justice Services has approved just 16 of 26 applications so far for genealogical DNA testing on samples gathered in criminal investigations. Parabon, on the other hand, would not be required to submit any applications to the state before analysing DNA evidence provided by law enforcement.

Authorities across the country have made dozens of cold-case arrests with the help of genetic genealogy, including the capture of the accused Golden State Killer. But the method has also sparked concern over the way public law enforcement agencies are using private DNA databases to catch offenders.

Here’s how Parabon’s work with New York law enforcement would be performed, according to Walsh:

An agency like the NYPD would consult with Parabon to determine whether it has enough DNA available for profiling.

If it does, the sample would be sent to a private lab like AKESOgen—a genetic analysis lab which which Parabon frequently works—where scientists would create a DNA profile with an accompanying trove of data.

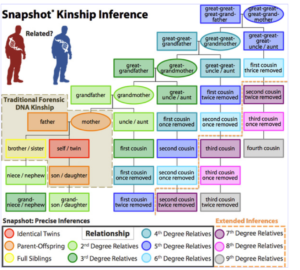

Parabon would then test that profile against public genealogical databases like GEDMatch, and use the genetic data to perform phenotyping: the prediction of physical appearance and ancestry of an unknown person from their DNA, as well as kinship inference analysis: the determination of kinship between DNA samples out to nine degrees of relatedness (fourth cousins).

“We will give Parabon, assuming that everything goes smoothly, a permit in forensic identity that’s limited to this investigative genetic genealogy and phenotyping, and kinship analyses,” Walsh, who is also a member of the state forensic science commission, said at the body’s June 7 meeting. “And we will hold them to all of the New York State and FBI standards that we see as applicable. But obviously, many of them are not going to be directly applicable.”

Parabon, based in Virginia, declined to comment on what kind of work it might perform in New York, citing the ongoing DOH review process. But the company has boasted of its ability to help solve decades-old cold cases.

Leads generated by Parabon have led to more than 55 “solves” for its customers since May 2018, the company said.

Dr. Ellen Greytak, who led the development of Parabon’s phenotyping and kinship inference technology, said Parabon has “developed innovative capabilities that allow us to succeed on samples where others may fail. Particularly for cases involving sexual assault, our ability to computationally isolate the genome-wide genotypes of a suspect, unique in the industry, is indispensable.”

In a recent press release, Parabon said research for many of its solved cases was “extraordinarily difficult, involving distant relationship matches, adoption, misattributed parentage, and/or pedigree collapse, any of which can stall a genetic genealogy investigation.”

While victim advocates have lauded Parabon’s technology as transformative, privacy and criminal defense experts fear a kind of national DNA dragnet could result from the company teaming up with New York law enforcement.

“Parabon, like many other for-profit DNA companies, performs boundary-pushing testing with little to no regard for the people who may be impacted by their results,” said Terri Rosenblatt, Supervising Attorney of the Legal Aid Society’s DNA Unit. “As a private company, Parabon’s procedures exist in a black box. Some methods, such as creating accurate virtual mugshots, rest, perhaps, on a kernel of truth, but distort the actual capability of current science. We hope the State insists on transparency, accountability and reliability from this company before its methods are used on New Yorkers.”

Walsh, in describing the oversight process for Parabon, told fellow commissioners that staffers at the company and its partner lab would be scrutinised.

“All of their methods and validations would be looked at. Their quality system would be looked at and they’d be inspected. They would be expected to do proficiency testing and they’d continue to have this review, at least an on-site audit every two years.”

“Parabon is going forward and submitting their protocols and their validation using various different DNAs and different agencies that they have worked with,” she added. “Once we’re satisfied that…they’re putting all of their policies and procedures in place and making sure that all of their staff members are trained and have been competency-tested and so forth, and we get to a certain point where we’re fairly sure they’re ready for an inspection, we’ll go on site and inspect them.”

“So, in terms of oversight they’ll have active oversight.”

Among the eleven members of the state forensic science commission in attendance at the June meeting, two expressed concerns about Parabon’s potential work in New York.

Dr. Ann Willey, former director of laboratory policy at the state’s public health lab in Albany, said experts “set up through the commission a familial search system where we’re asking the investigators to tell us exactly why they want to [use genealogical DNA testing], and we’re incorporating the training component on the other end.”

Currently, New York state allows law enforcement agencies to perform familial searches using the state’s DNA Databank, which contains more than 682,000 profiles from people convicted of felonies and misdemeanors.

Parabon, on the other hand, would be “searching all relatives in these genealogical databases…a huge profile of DNA elements, hundreds of thousands…so once they’re approved in New York we can anticipate investigators, I think, doing a parallel search. And it’s just a thought that, having gone to all the trouble of developing the training program, sharing that, at least, with Parabon.”

Willey added: “I think we will potentially encounter the…forensics lab or investigator making a request for familial search through the DCJS system at the same time that they say ‘I got lots of DNA left, I’m not going to wait for that process…I’m going contact Parabon and I’m going to ask them if I have enough DNA, can I…get another set of data working through a totally different data analysis system. It may find the same families. But our family database is really small. It’s convicted offenders.”

David Loftis, Attorney-in-Charge of Post Conviction and Forensic Litigation for the Legal Aid Society, questioned whether the potential for solving certain crimes would be worth the privacy tradeoffs.

“You’re doing six generations away, and then you show up at somebody’s doorstep, it seems like a low probative value where you’re collected in some sort of vast dastasbase,” said Loftis, a commission member and former managing attorney for the Innocence Project.

Attorney Michael Green, chairman of the commission, dismissed the concerns of both Willey and Loftis.

“DCJS, as I see it, doesn’t have a formal role,” said Green. “We don’t have any authority to assert ourself.”

Added Walsh: “And our authority is also really limited to what the jurisdiction fo the lab is. And so we can’t dictate to law enforcement officers, like, what types of crimes should qualify or anything like that, so there isn’t a mechanism to set up something like we have with familial DNA.”

Parabon, which originally created its technology for the federal government in order to identify dead suicide bombers using their DNA, has worked with the NYPD before.

In 2017, the company helped create a DNA profile for an unidentified, dismembered woman found murdered in Brooklyn. The company also helped the NYPD create a sketch of a man found murdered in 2005.

Parabon’s most recent success came last month in Washington state, where prosecutors earned a conviction in a 1987 murder solved with the help of Parabon’s genealogical DNA technology. The company used GEDMatch’s public database to help crack the case, which marked the first time the technique went before a jury.

This story has been updated.