By Eric Klein and Kevin Deutsch

[email protected] , [email protected]

The operator of the Bronx Zoo apologized this week for “unconscionable racial intolerance” the zoo demonstrated when it exhibited an African man as an exotic animal and promoted the long-debunked study of racial science known as eugenics.

The two episodes, according to the Wildlife Conservation Society, showed despicable racism, the organization said in a statement, marking the first time it’s apologized for the well-documented acts of hate.

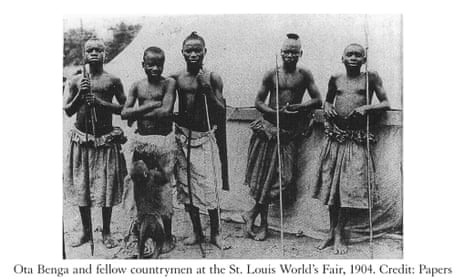

“First, we apologize for and condemn the treatment of a young Central African from the Mbuti people of present-day Democratic Republic of Congo,” the society said in its statement, referring to the kidnapping and exhibiting of Ota Benga, who was displayed with monkeys as an exotic animal at the world-famous zoo. “Bronx Zoo officials, led by Director William Hornaday, put Ota Benga on display in the zoo’s Monkey House for several days during the week of September 8, 1906 before outrage from local Black ministers quickly brought the disgraceful incident to an end and the Reverend James Gordon arranged for Ota Benga to stay at an orphanage he directed in Weeksville, Brooklyn. Robbed of his humanity and unable to return home, Ota Benga tragically took his life a decade later.”

The zoo said it also wished to “apologize for and condemn bigoted actions and attitudes” in the early 1900s toward non-whites—especially African Americans, Native Americans and immigrants—“that characterized many notable institutions at the time, including our own.“

“Specifically, we denounce the eugenics-based, pseudoscientific racism, writings, and philosophies advanced by many people during that era, including two of our founders, Madison Grant and Henry Fairfield Osborn, Sr. Excerpts from Grant’s book “The Passing of the Great Race” (with a preface by Osborn), were included in a defense exhibit for one of the defendants in the Nuremberg trials,” the society said in its apology. “Grant and Osborn were likewise among the founders of the American Eugenics Society in 1926.

“We deeply regret that many people and generations have been hurt by these actions or by our failure previously to publicly condemn and denounce them.”

The society said it was making all known records in its possession related to Ota Benga available online, and would develop additional projects to “make our history accessible and transparent, especially to outside writers and researchers.”